Remembering

The Melbourne School for Enrolled Nurses

‘I believe that the role of the State Enrolled Nurse lies in partnership with the Registered General Nurse – each needs the other but the patient needs them both.’

Thirty years ago, the newly elected Kennett Government slammed shut the doors on the Melbourne School for Enrolled Nurses, closing an important chapter in Victorian nursing history.

The school, run largely by and for women throughout its lifetime, had for 40 years not only led and innovated the training of enrolled nurses but also enhanced and secured their place within the profession.

The story of enrolled nurses in Victoria began in earnest after World War II. During the war, patriotic fervour saw many women untrained in nursing – or, perhaps, anything other than domestic work – join Voluntary Aid Detachments where they gained hospital experience. ‘When these women are demobilised,’ noted Gwen Burbidge in 1943, ‘thousands who have hospital experience will be available for caring for the sick … In fairness to our nurses training today and in days to come, we who can see ahead must move and move now to define the position of the great army of women that will pour into the hospital world.’1

But despite ‘a desperate shortage of trained nurses in Victoria in the immediate post-war years’2, the Royal Victorian College of Nursing (RVCN) was opposed to embracing the influx of now semi-trained women returning home, and stymied any attempts to do so. Accepting these ‘earnest, sparetime amateurs’ would be ‘professional suicide’3 according to Jane Bell, president of the RVCN.

In 1950, with the nursing shortage showing no sign of abating, the Hospitals and Charities Commission – the newly formed body responsible for management of Victoria’s hospitals as well as the recruitment and training of nurses – finally agreed to classify nurses into two divisions: registered nurses who undertook highly skilled nursing work, and nursing aides who did routine care. Nursing aides were to be recruited from citizens, including the women who served during the war, as well as from the so-called New Australians: young immigrant women who had escaped war-torn Europe.

Burbidge, long-time matron of Fairfield Hospital and renowned for her work to improve professional and educational conditions for Australian nurses4, had been instrumental in the decision. The first Australian nurse to receive a Rockerfeller Foundation scholarship to study nurse training courses in America, on her return to Melbourne she was ‘able to convince the chairwoman of the Hospitals and Charities Commission to set up training courses for nursing aides.’5

New Australians at the official opening of the Nursing Aide School. Photo: The Age, 4 October 1950

New Australians at the opening of the Nursing Aide School. Photo: The Age, 4 October 1950

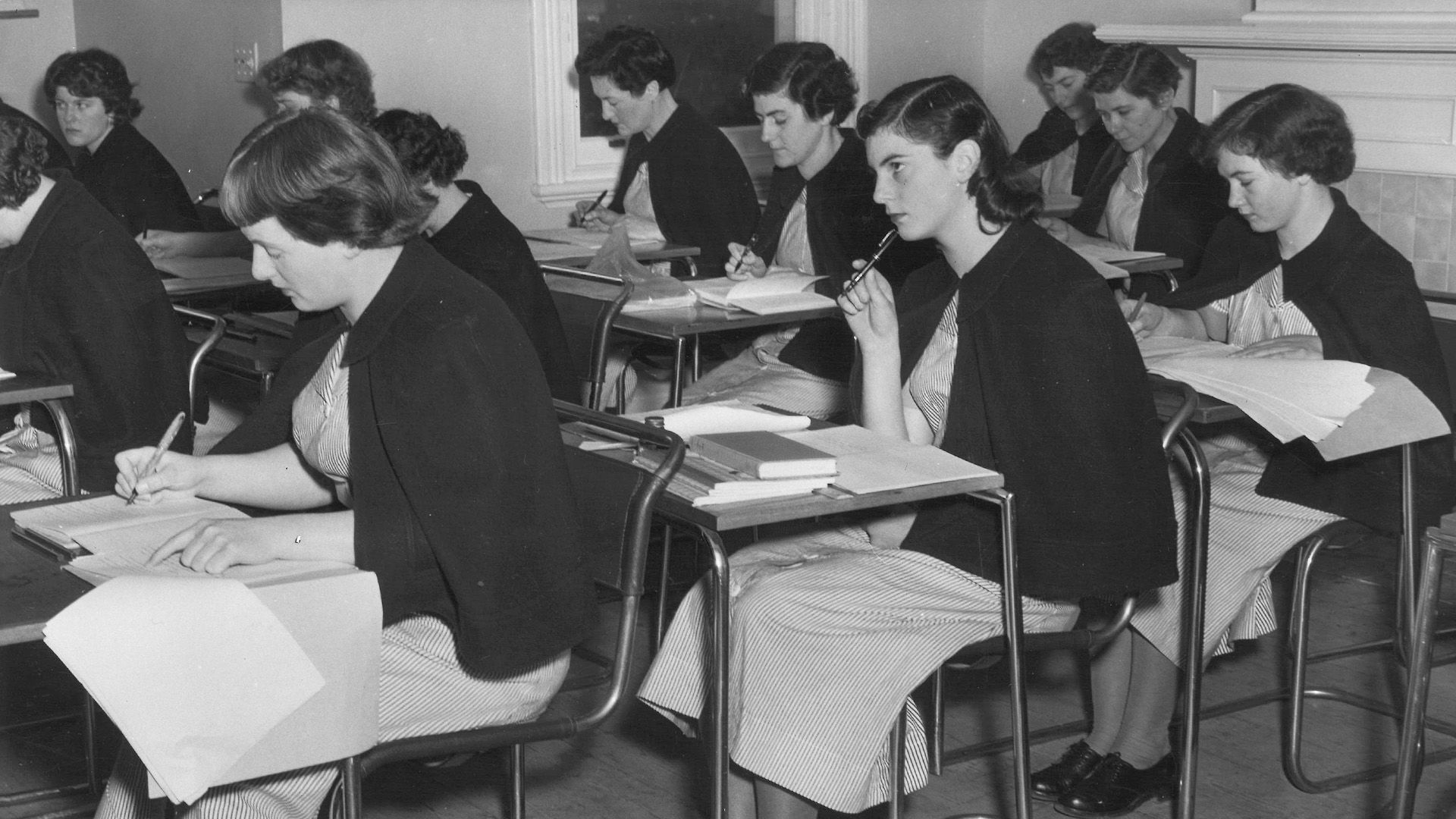

Students in class. Photo: Roy Dunstan (Nursing Aide School Annual Report 1955-56)

Students in class. Photo: Roy Dunstan (Nursing Aide School Annual Report 1955-56)

An early 'capping' ceremony at the Nursing Aide School in the 1950s. Photographer unknown

An early 'capping' ceremony at the Nursing Aide School in the 1950s. Photographer unknown

A turning point: the first of its kind

The Nursing Aide School opened in Toorak in October 1950, with Burbidge as chair of its management committee.

The first school of its kind in Australia, it ‘represented a turning point in the history of the Australian nursing profession’6. Primarily for New Australian students, it offered classes in English as well simple nursing duties. Students lived onsite, before completing their training in an affiliated hospital.

By 1953, a further 15 nursing aide training institutions were operating around the state, but the original Melbourne school continued to lead the way. In 1962, for instance, the Hospitals and Charities Commission published Vera Jackson’s Handbook for Nursing Aides, which was based upon lectures given at the school. Two years later, copies were being used in all Australian states, as well as in New Zealand, the UK, Hong Kong and India.

The school’s students followed suit, advocating for better conditions in their work and more respect. They organised and participated in some of the first successful industrial action by nursing aides, seeking more equitable pay – in the 1960s, female nursing aides earned about $10 a week less than their male counterparts; and all were paid barely more than unskilled hospital workers – and called for changes to the curriculum to enable them to undertake more advanced duties.

An image from the Melbourne Nursing Aide School annual report 1958-59. Photo by Bryan V Ruffin

An image from the Melbourne Nursing Aide School annual report 1958-59. Photo by Bryan V Ruffin

An image from the Melbourne Nursing Aide School annual report 1958-59. Photo by Bryan V Ruffin

An image from the Melbourne Nursing Aide School annual report 1958-59. Photo by Bryan V Ruffin

The Nursing Aide School opened in Toorak in October 1950, with Burbidge as chair of its management committee.

The first school of its kind in Australia, it ‘represented a turning point in the history of the Australian nursing profession’6. Primarily for New Australian students, it offered classes in English as well simple nursing duties. Students lived onsite, before completing their training in an affiliated hospital.

By 1953, a further 15 nursing aide training institutions were operating around the state, but the original Melbourne school continued to lead the way. In 1962, for instance, the Hospitals and Charities Commission published Vera Jackson’s Handbook for Nursing Aides, which was based upon lectures given at the school. Two years later, copies were being used in all Australian states, as well as in New Zealand, the UK, Hong Kong and India.

The school’s students followed suit, advocating for better conditions in their work and more respect. They organised and participated in some of the first successful industrial action by nursing aides, seeking more equitable pay – in the 1960s, female nursing aides earned about $10 a week less than their male counterparts; and all were paid barely more than unskilled hospital workers – and called for changes to the curriculum to enable them to undertake more advanced duties.

A student completes a test. Photo: Bryan V Ruffin (Nursing Aide School annual report, 1968-69)

A student completes a test. Photo: Bryan V Ruffin (Nursing Aide School annual report, 1968-69)

Students in uniform at the entrance to main hostel. Photo: Nursing Aide School annual report 1961-62

Students in uniform at the entrance to main hostel. Photo: Nursing Aide School annual report 1961-62

Students learning about bathing the baby. Photo: Nursing Aide School annual report 1962-63

Students learning about bathing the baby. Photo: Nursing Aide School annual report 1962-63

From nursing aides to enrolled nurses

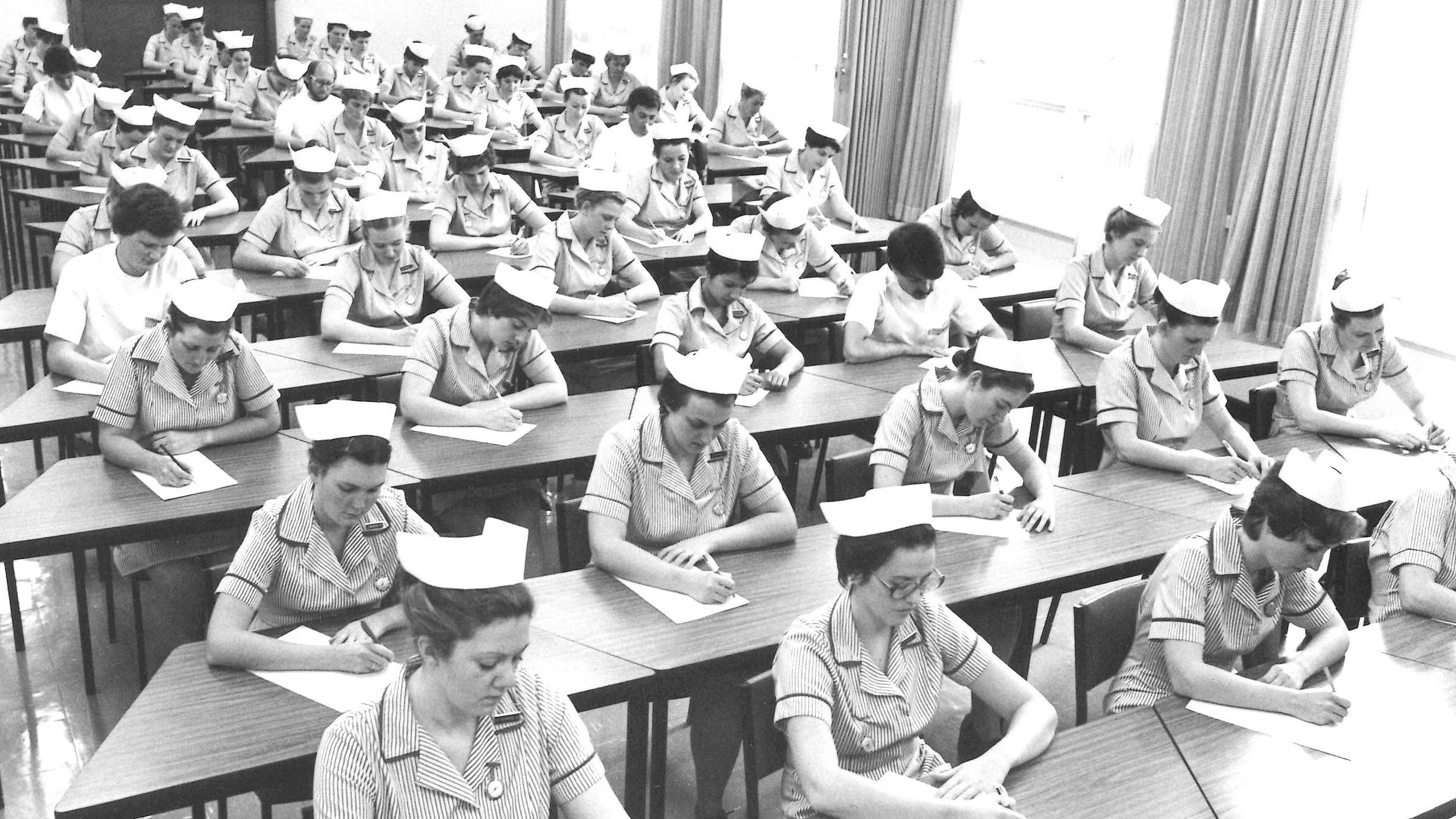

The students on Sunday

The students on Sunday

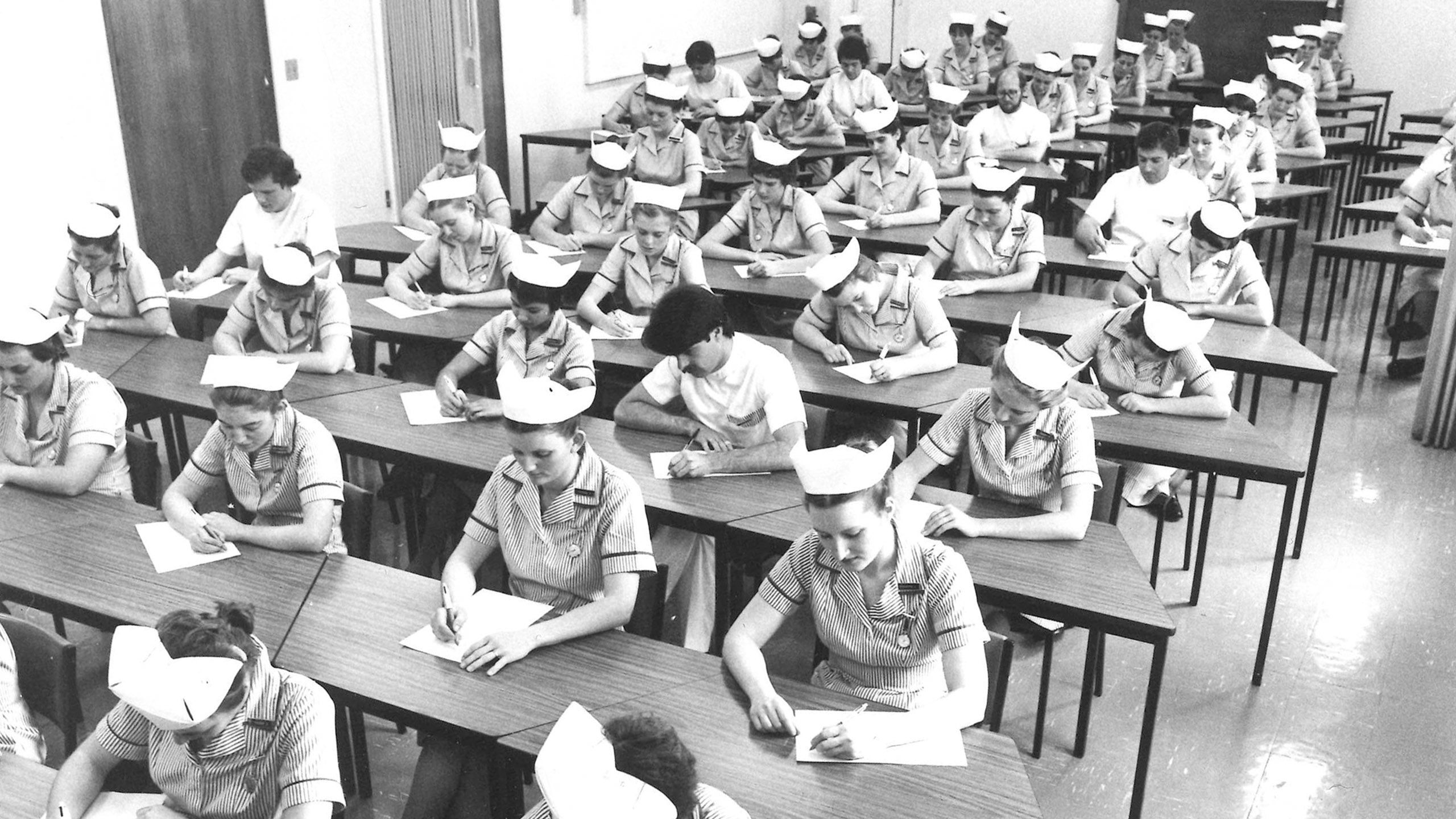

The students on Monday

The students on Monday

Since the implementation of the Nurses’ Act 1956, the Victorian Nursing Council (formerly, the Nurses Board) had ultimate control over training, qualifications and registration of Victorian nurses and nursing aides, and was thus responsible for the state curriculum taught by the Melbourne Nursing Aide School.

By the late ‘60s this curriculum was creaky and in 1970 the report of the Committee of Enquiry into Nursing in Victoria echoed the students and recommended a more advanced programme of studies for nursing aides.

Among its reasons were that almost 90 per cent of nursing aides reported being required to administer medicines, despite the curriculum not preparing them for this. The fifth of the report’s seven main recommendations noted that ‘the current nursing aide training should be replaced as a matter of urgency by a more advanced programme of training and the title of those qualifying from the new course should be Enrolled Nurse.’7

In 1971, the Minister for Health announced an advanced training course, but a curriculum had yet to be devised. The Melbourne Nursing Aide School stepped up, convening an education advisory committee to draft a new curriculum, and provide recommendations to the Victorian Nursing Council. Unfortunately, it would take another two decades before the revised curriculum was officially implemented – much to students’ and the school’s frustration. Part of the delay was economic, with concerns that implementation of a new curriculum would necessitate extra staff, facilities and classroom time, and ultimately incite industrial action for increased wages.

There were some wins. The term Enrolled Nurse was finally adopted in 1981 and with it the school became the Melbourne School for Enrolled Nurses. But as the years wore on with no new curriculum in sight, it faced an uncertain financial future. A management consultant suggested it be merged with another training institution. In the background, investigations were ongoing to bring all state enrolled nurse training into the TAFE system.

Ultimately, it was the 1986 nurses and midwives strike that broke the stalemate. ‘On 12 December … the Minister for Health, David White, in a step which was seen by many people as provocative and controversial, took over the Victorian Nursing Council’s powers and extended the duties of state enrolled nurses in an attempt to break the strike.’8 The decision only lasted a day, but it lit a fire and a few months later the Health Department convened the Victorian Nursing Council, the Victorian Hospitals’ Association, RANF (Vic Branch), the AMA and others, and a pilot course – to be run by the Melbourne School for Enrolled Nurses – was planned for 1989, though ultimately was delayed until 1990.

The course was a success, but it couldn’t save the school. Falling enrolments continued to hamper the bottom line, and the push for enrolled nurse training via TAFE colleges – and ultimately the tertiary sector – continued. Cuts in health services funding didn’t help and then, in 1992 with the election of Jeff Kennett, the school’s fortunes were all but sealed. Just six weeks later, the Kennett Government closed the Melbourne School of Enrolled Nurses for good.

Since the implementation of the Nurses’ Act 1956, the Victorian Nursing Council (formerly, the Nurses Board) had ultimate control over training, qualifications and registration of Victorian nurses and nursing aides, and was thus responsible for the state curriculum taught by the Melbourne Nursing Aide School.

By the late ‘60s this curriculum was creaky and in 1970 the report of the Committee of Enquiry into Nursing in Victoria echoed the students and recommended a more advanced programme of studies for nursing aides.

Among its reasons were that almost 90 per cent of nursing aides reported being required to administer medicines, despite the curriculum not preparing them for this. The fifth of the report’s seven main recommendations noted that ‘the current nursing aide training should be replaced as a matter of urgency by a more advanced programme of training and the title of those qualifying from the new course should be Enrolled Nurse.’7

In 1971, the Minister for Health announced an advanced training course, but a curriculum had yet to be devised. The Melbourne Nursing Aide School stepped up, convening an education advisory committee to draft a new curriculum, and provide recommendations to the Victorian Nursing Council. Unfortunately, it would take another two decades before the revised curriculum was officially implemented – much to students’ and the school’s frustration. Part of the delay was economic, with concerns that implementation of a new curriculum would necessitate extra staff, facilities and classroom time, and ultimately incite industrial action for increased wages.

There were some wins. The term Enrolled Nurse was finally adopted in 1981 and with it the school became the Melbourne School for Enrolled Nurses. But as the years wore on with no new curriculum in sight, it faced an uncertain financial future. A management consultant suggested it be merged with another training institution. In the background, investigations were ongoing to bring all state enrolled nurse training into the TAFE system.

Ultimately, it was the 1986 nurses and midwives strike that broke the stalemate. ‘On 12 December … the Minister for Health, David White, in a step which was seen by many people as provocative and controversial, took over the Victorian Nursing Council’s powers and extended the duties of state enrolled nurses in an attempt to break the strike.’8 The decision only lasted a day, but it lit a fire and a few months later the Health Department convened the Victorian Nursing Council, the Victorian Hospitals’ Association, RANF (Vic Branch), the AMA and others, and a pilot course – to be run by the Melbourne School for Enrolled Nurses – was planned for 1989, though ultimately was delayed until 1990.

The course was a success, but it couldn’t save the school. Falling enrolments continued to hamper the bottom line, and the push for enrolled nurse training via TAFE colleges – and ultimately the tertiary sector – continued. Cuts in health services funding didn’t help and then, in 1992 with the election of Jeff Kennett, the school’s fortunes were all but sealed. Just six weeks later, the Kennett Government closed the Melbourne School of Enrolled Nurses for good.

Students studying the circulation of blood. Photo: Bryan V Ruffin (Melbourne Nursing Aide School, 1972)

Studying the circulation of blood. Photo: Bryan V Ruffin (Melbourne Nursing Aide School, 1972)

An anatomical discussion. Photo: Bryan V Ruffin (Melbourne Nursing Aide School annual report, 1979-80)

An anatomical discussion. Photo: Bryan V Ruffin (Melbourne Nursing Aide School annual report, 1979-80)

Gloria Wales, Marie Renowden, Heather Mckenzie, Hilda Hepburn and Gail Hoskin all returned to nursing after marriage. Photographer unknown, October 1975

Heather Mckenzie, Hilda Hepburn and Gail Hoskin, October 1975

From little things big things grow

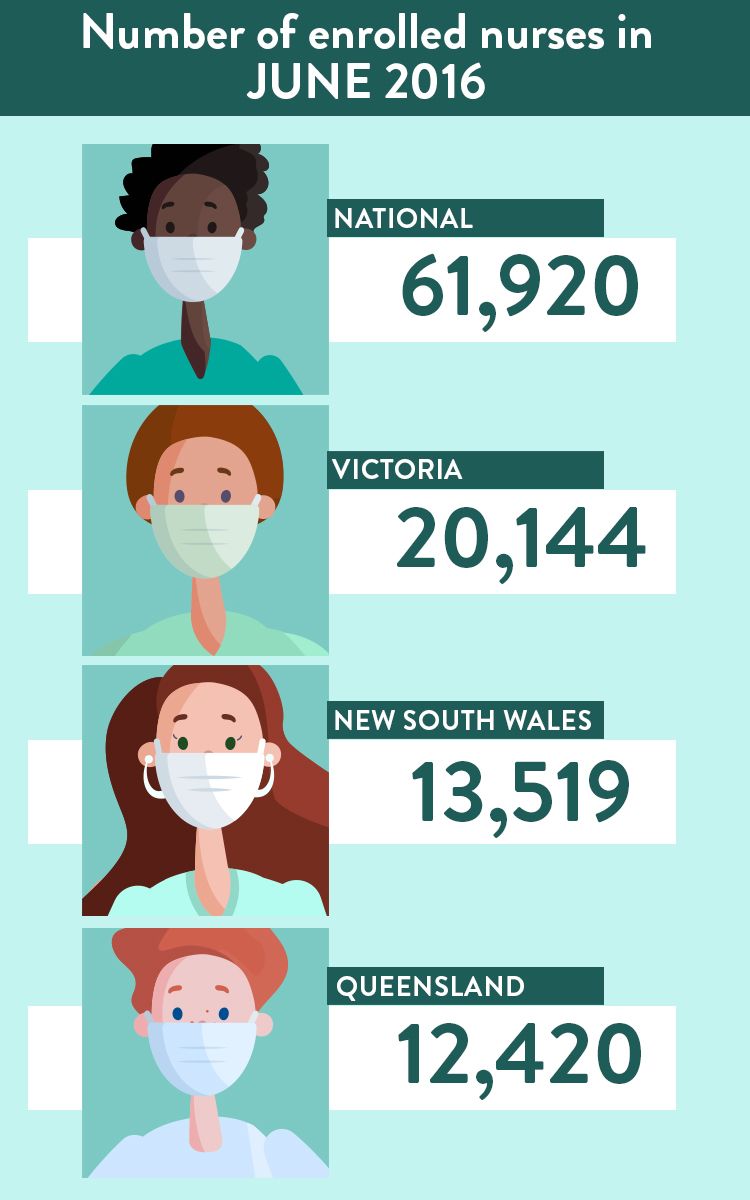

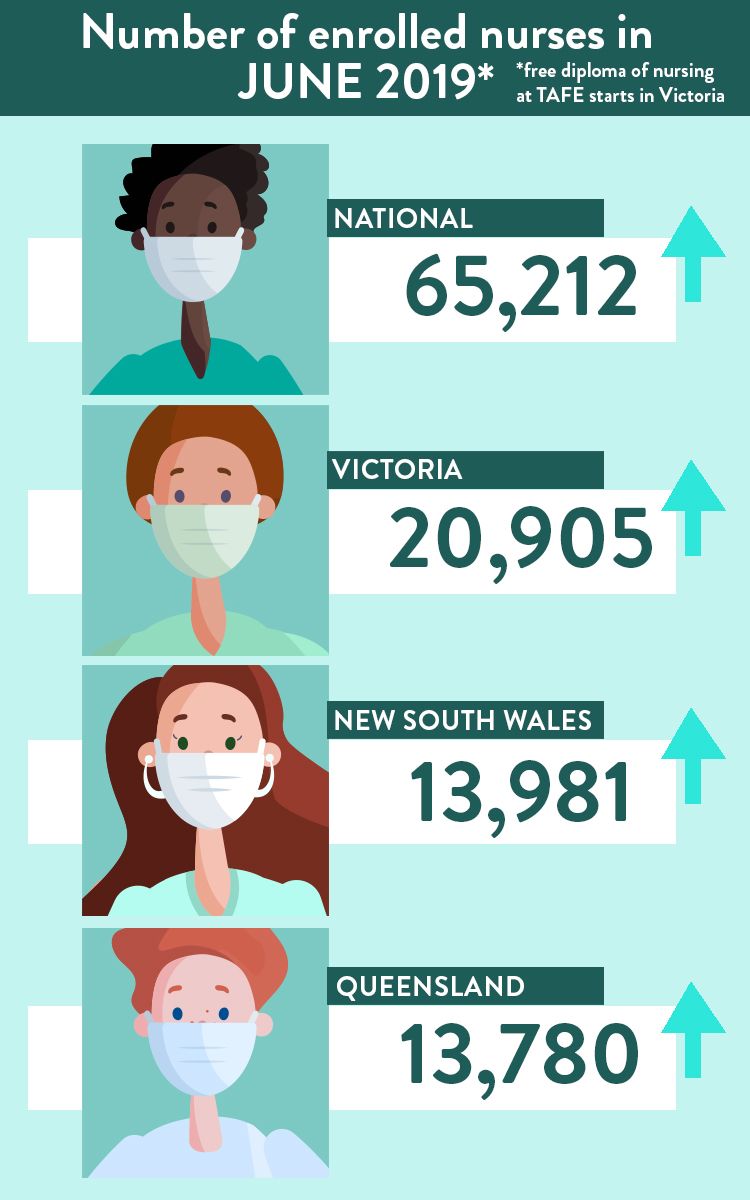

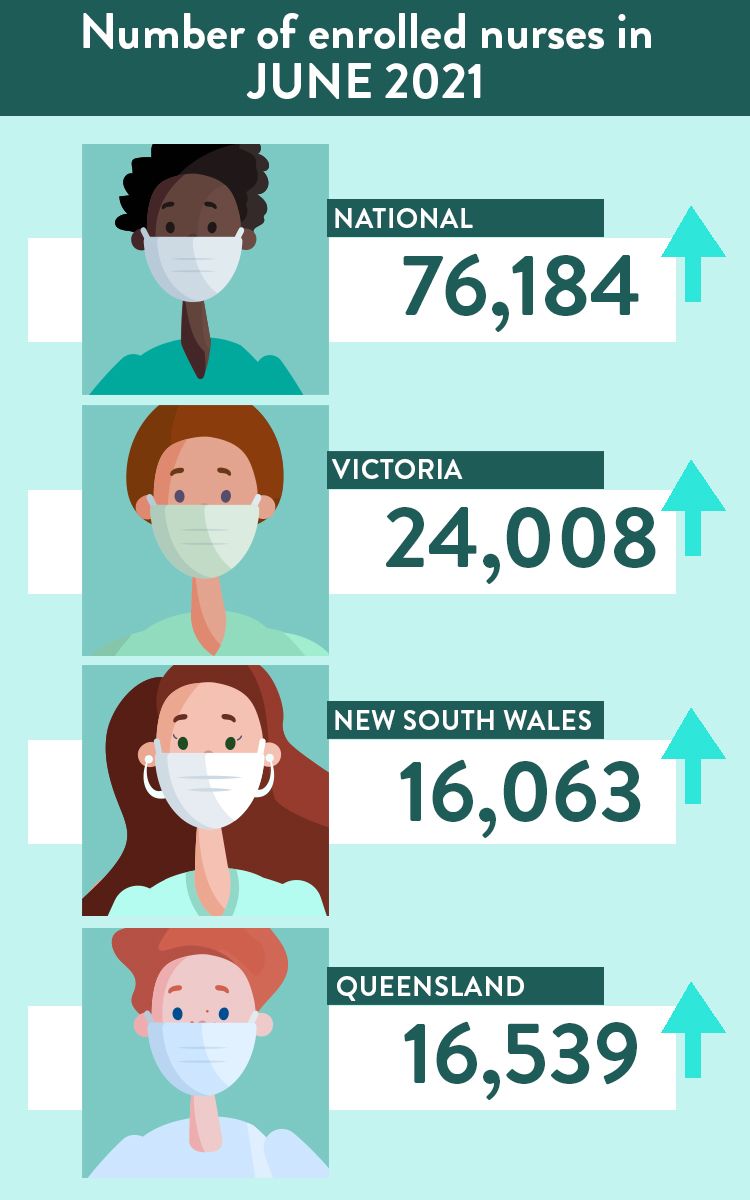

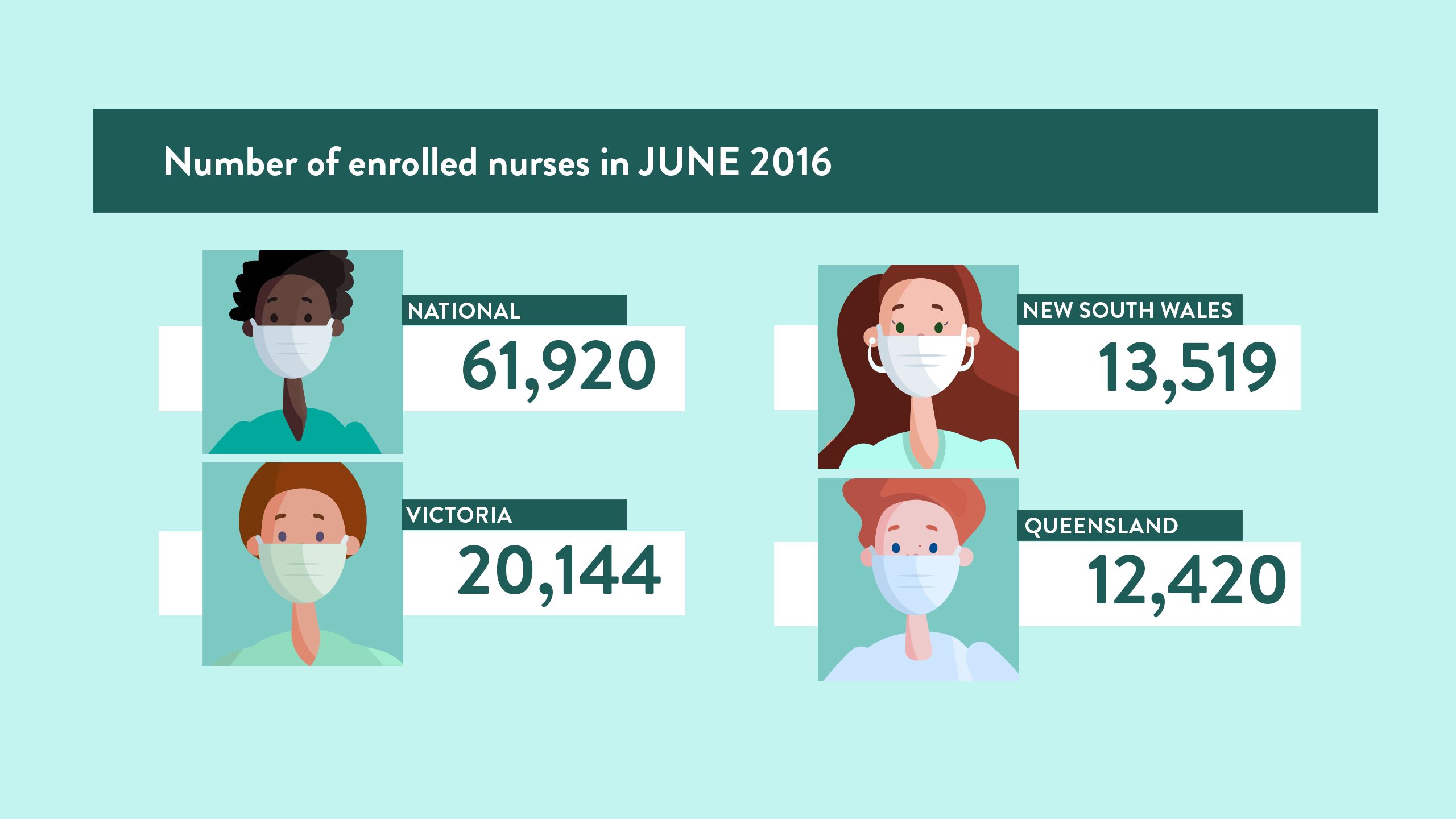

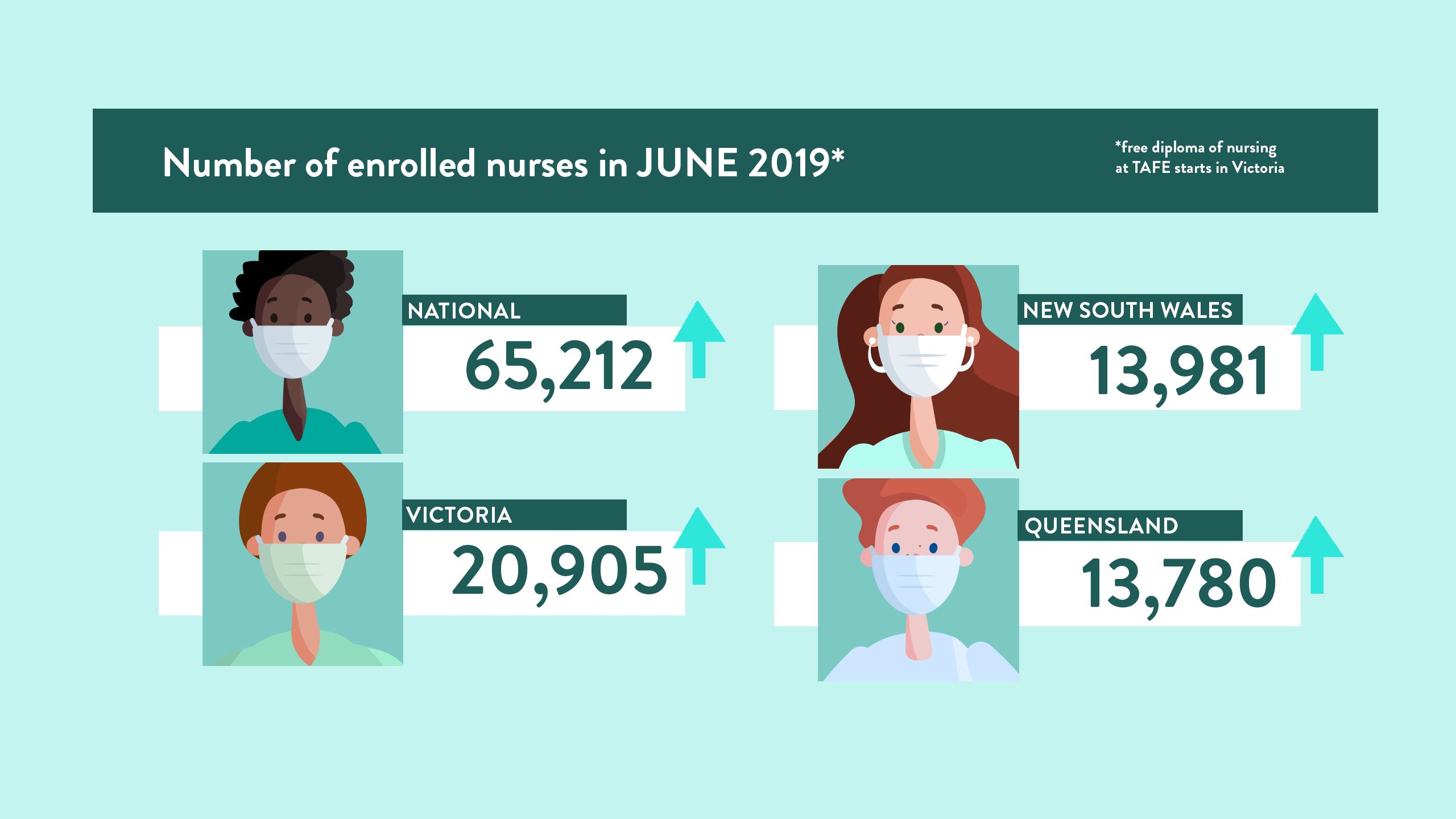

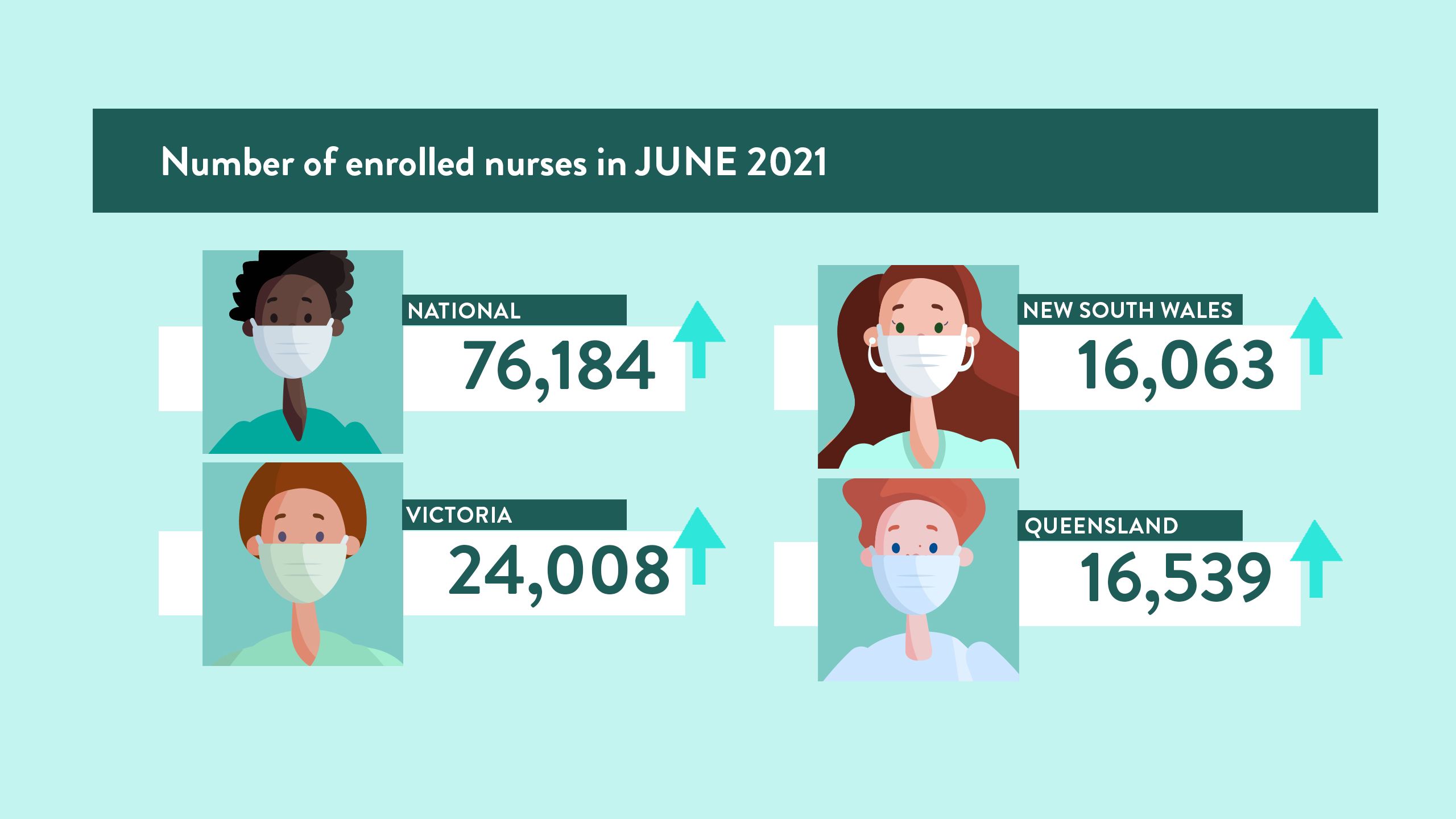

Having led the way in the history of enrolled nursing in Australia, Victoria today has the largest – and fastest growing – number of enrolled nurses in the country.

This is a legacy of the hard work and dedication of a number of active enrolled nurses, and their special interest group, who championed the importance of their role in the 1990s and 2000s. After the Kennett years, ANMF (Vic Branch) and enrolled nurses secured commitments from successive Victorian governments to expand enrolled nurse education opportunities.

In 2019, the Andrews Government made the diploma of nursing free at public TAFE as part of its plan to build a skilled workforce in priority areas. It also announced a $50 million nursing and midwifery workforce development fund that included additional transition to practice programs which will see four hundred new enrolled nurses employed between 2019 and 2023, once they successfully complete their free diploma.

The free education and enrolled nurse transition to practice programs will be particularly important to meet the new workforce care-minute mandates and skill mix in private aged care required from the yet-to-be written new federal aged care legislation and the aged care royal commission. It will be important we do not lose this pool of new enrolled nurses.

ANMF continues to campaign for the urgent implementation of improved staffing and skill mix inclusive of registered and enrolled nurses and personal care workers in private aged care.

Having led the way in the history of enrolled nursing in Australia, Victoria today has the largest – and fastest growing – number of enrolled nurses in the country.

This is a legacy of the hard work and dedication of a number of active enrolled nurses, and their special interest group, who championed the importance of their role in the 1990s and 2000s. After the Kennett years, ANMF (Vic Branch) and enrolled nurses secured commitments from successive Victorian governments to expand enrolled nurse education opportunities.

In 2019, the Andrews Government made the diploma of nursing free at public TAFE as part of its plan to build a skilled workforce in priority areas. It also announced a $50 million nursing and midwifery workforce development fund that included additional transition to practice programs which will see four hundred new enrolled nurses employed between 2019 and 2023, once they successfully complete their free diploma.

The free education and enrolled nurse transition to practice programs will be particularly important to meet the new workforce care-minute mandates and skill mix in private aged care required from the yet-to-be written new federal aged care legislation and the aged care royal commission. It will be important we do not lose this pool of new enrolled nurses.

ANMF continues to campaign for the urgent implementation of improved staffing and skill mix inclusive of registered and enrolled nurses and personal care workers in private aged care.

References

1. Judith Bessant and Bob Bessant, The Growth of a Profession: Nursing in Victoria 1930s–1980s (La Trobe University Press, 1992), p17

2. Jan Bassett, Nursing Aide to Enrolled Nurse: A History of the Melbourne School for Enrolled Nurses (Melbourne School for Enrolled Nurses, 1993), p8

3. ibid., p6

4. Judith Godden, Australia’s Controversial Matron: Gwen Burbidge and Nursing Reform (The College of Nursing, Sydney, 2011)

5. Bessant and Bessant, op. cit., p77

6. Bassett, op. cit., p1

7. ibid., p47

8. ibid., p77