The great decline of infant mortality

By 1926, the infant mortality rate had been reduced by half and there had been a dramatic decline in deaths from gastrointestinal diseases. By this stage, the baby welfare service was nearly a decade old and sanitation, such as the systematic collection and removal of ‘nightsoil’, had improved.

Improvements in the quality of water and milk supplies, an increase in breastfeeding, better access to education and a decreasing number of births per woman were other factors likely to have contributed to the dramatic declines in child deaths. (Stanley 2001).

Eugene gets weighed at the Bellfield Maternal and Child Health Centre.

At the beginning of Federation in 1901 the Australian infant mortality rate per 1000 live births – the number of babies who died before their first birthday – was 120 for boys and 100 for girls. (Stanley 2001).

In 2014, the infant mortality rate was 3.4, a decline of 95 per cent since 1904 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare). More than 50 per cent of the decline in infant deaths had occurred by 1930 and 80 per cent by 1960 (Stanley 2001).

Baby opens door to a bottle of milk delivered.

By the 1930s, less than a third of infant deaths were post-neonatal. In the 1940s and 1950s, as mass vaccination and antibiotics became available, the number of infant deaths dropped still further. (Stanley 2001).

The power of many – how baby health centres spread across Victoria

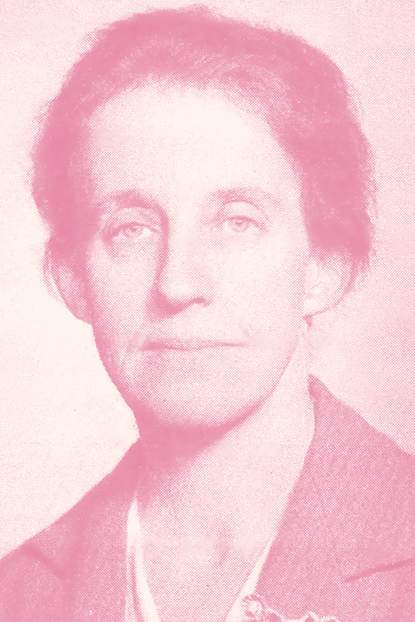

Born of the persistence and lobbying of its Infant Welfare Society founders, the Maternal and Child Health Service thrived under the formidable duo of Dr Vera Scantlebury Brown and Sister Muriel Peck, as director and assistant director of the Department of Infant Welfare. These women gave their lives to improving the health system for children and mothers.

Dr Vera Scantlebury Brown.

But the rapid spread of baby health centres across Victoria, mobile services to rural families, and the availability of 24/7 advice and support to parents via the Maternal and Child Health Line, owes much to the organising power and voluntary work of hundreds of women.

The following Victorian Heritage Council account of the birth of the Echuca Baby Health Centre in 1925 demonstrates the efficacy of women working together to establish centres in their local areas (Heritage Council of Victoria 2005) :

The Echuca Movement

On 25 March 1925 following petitions from Mrs McBride, the Mayoress of Echuca and many other ladies anxious to start a local baby health centre, Sister Muriel Peck, propaganda officer for the voluntary group Victorian Baby Health Centres Association (VBHCA), addressed the Echuca Borough Council and subsequently a public meeting of Echuca women.

This prompted the council to agree to share with the State the cost of an infant welfare sister's salary and to place a room at her disposal. The Echuca Baby Health Centre Committee was formed on 14 May 1925 to organise and oversee its running. The committee ladies donated many of the items needed to set it up and purchased the rest with the 30 pounds offered by the VBHCA to equip all new centres.

Ladies were organised to drive the sister on her visits and the local registrar was approached for lists of new births. The selection of a sister was made by Mrs C. White, Secretary of the VBHCA. When Sister Rodda arrived to take up her duties on 15 October, an official opening for the centre was already arranged for 17 November.

The Ladies Committee of the Baby Health Centre at Red Cliffs on receipt of donations. Courtesy of the State Library of Victoria.

The committee had also approached the local school principal to allow the sister to undertake a series of lectures in mothercraft for the senior girls and had organised a roster of volunteers to help at the centre. Sister Peck visited and demonstrated the benefits of an insect-proof cot she had invented in which a child may stand with 'no danger of falling out'.

A milk cooler made from a kerosene tin and towelling was also demonstrated to mothers unable to obtain ice or afford ice chests.

Sister Edith Dawson arrived in April 1929. Intending to stay for only three to six months, she remained for sixteen years. In October 1930 she reported that 75 per cent of babies attending the centre were now breast fed, an increase of 25 per cent since the centre’s first annual report.

On leaving Echuca to work with Dr Scantlebury Brown in 1944 Sister Dawson reflected:

‘One felt one had done wonders if she had shown the mother how to produce a cool safe from the old fashioned kerosene tin; given some gentle stimulation to assist breast supply, washed an odd napkin or two, plus the baby. In short, given complete moral and down to earth support to a weary mother... In my 16 years at Echuca there was a drought, the depression and second world war.’

Video: Consolidation and conflict.

Throughout the life of Victoria’s Maternal and Child Health Service, those who understand the breadth of the nurse’s role have pushed for uniform education and professional standards.

In 1926, doctors Vera Scantlebury Brown and Henrietta Main, following their inquiry into the welfare of women and children, recommended the development of a standardised infant welfare curriculum and a uniform qualification for all nurses in baby health centres. The Main and Scantlebury report also recommended that infant welfare schools be established and expanded (Main and Scantlebury 1926).

Maternal and Child Health Centre. Courtesy of the Queen Elizabeth Centre.

Despite the report’s recommendation that acrimony cease between the Victorian Baby Health Centres Association and the Society for the Health of the Women and Children in Victoria, it continued with the establishment of rival training schools.

The VBHCA opened a training school in South Melbourne in 1920, with Sister Muriel Peck as matron providing three months intensive training to nurses. Trainees had to be a registered nurse with preference given to nurses with midwifery certificates and those with war service (Crockett 2000). Doctors, including Dr Vera Scantlebury, gave lectures (alongside supervising all the baby health centres).

Victorian Baby Health Centre Association and Mothercraft Home at the Women's Hospital. Courtesy of the Queen Elizabeth Centre.

In 1922 the Society for the Health of the Women and Children – overseen by New Zealand psychiatrist Dr Truby King – opened its first training school in Footscray, the Tweddle Baby Hospital and School of Infant Welfare and Mothercraft.

Named after the school’s benefactor, the businessman J.L. Tweddle, the hospital provided accommodation for 12 nurses, eight babies and two nursing mothers (Flood 1998).

Baby gets weighed by maternal and child health nurse Jan Shaddock, 1995. Courtesy of the Public Record Office Victoria.

The residential school provided four to six months training under medical supervision. Kathleen Kehoe, already a registered nurse and midwife, took unpaid leave for four months to complete the training course at the Tweddle school.

Video: From strength to strength part one.

The Victorian Baby Health Centres Association opened a residential training school – the VBHCA Training School and Mothercraft Home – in Carlton in 1928. The course was four months, with doctors such as Dr Younger Ross and Dr Kate Campbell lecturing to trainee nurses at the school and giving Saturday morning lectures to nurses and doctors at the Children’s Hospital.

The site was later redeveloped as The Queen Elizabeth Hospital for Mothers and Babies, which opened in December 1951 (Crockett 2000).

The role of the maternal and child health nurse developed beyond ensuring babies’ survival to encompass more complex community needs, and the Victorian population both increased and diversified, with arrivals of immigrants and refugees.

Baby in consultation with maternal and child health nurse, with help from an interpreter, 1995. Courtesy of the Public Record Office Victoria.

The maternal and child health nurses’ ANMF special interest group, now known as the Victorian Association of Maternal and Child Health Nurses (VAMCHN), recognised the increasing complexity of maternal and child health nursing, lobbied for increased education. The four month infant welfare course ended in 1980, replaced with a 12 month diploma. From 1990 education for maternal and child health nurses was offered as a graduate diploma in child and family health nursing.

VAMCHN, established in the early 1940s, produced professional standards and guidelines for maternal and child health nurses in 1993. The standards were updated in 1999 following a participatory action research project. VAMCHN revised competency standards for maternal and child health nurses in 2010 and introduced documentation standards in 2016.

The 13 competency standards include promoting the role of the family in the health and development of the child, breastfeeding, maternal health and wellbeing, and appropriate nutrition (Competency Standards for the Maternal and Child Health Nurse in Victoria 2010).

Where babies are, the nurses will go

Between the opening of the first baby health centre in 1917 and 1926 - just under a decade - 62 centres, including 19 sub-centres, had opened in Victoria. Mobile services established by the Victorian Baby Health Centres Association provided advice and baby nursing care to isolated country families but also served to promote the baby health centres (Sheard 2007).

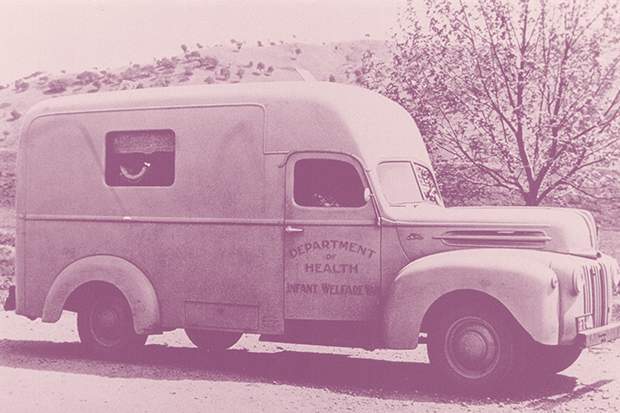

Department of Health Infant Welfare Van and a group of mothers and infants at Bethanga circa 1940s. Courtesy of the Public Record Office Victoria.

By 1944, there were well over 150 centres in metropolitan and country Victoria (Heritage Council of Victoria 2005).

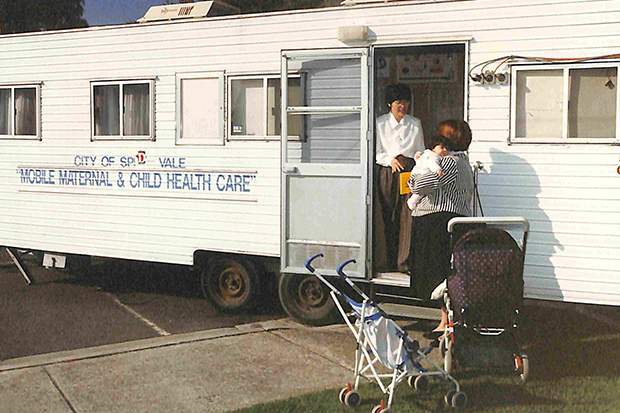

The mobile services – along with the Maternal and Child Health Line and the Enhanced Maternal and Child Health Service established later – demonstrated the commitment of maternal and child health nurses to providing care and advice to Victorian families wherever and whenever they were needed.

Margaret Walshe was a registered nurse and midwife, and had spent more than seven years in charge of operating theatre suits at Wangaratta Base Hospital before doing her infant welfare training in 1963. After training, she worked as an infant welfare nurse in Wangaratta.

She recalled: ‘Directions when home-visiting rural families were often interesting and confusing, particularly when lost and given directions by a farmer! “Go past Joe Brown’s wheat crop…don’t you know Joe Brown? Then turn left at the peppercorn tree near Bill Smith’s dairy, just past Jack White’s haystack…’

Ms Walshe also remembered an Italian father’s insistence that she toast the health of his newborn twin sons.

‘I finally agreed to a very small drink of purple liquor only to discover I had only toasted the firstborn; as father left the room to get more liquor I was quickly able to dispose of the remains in my glass into a nearby potplant.’

The Better Farming Train

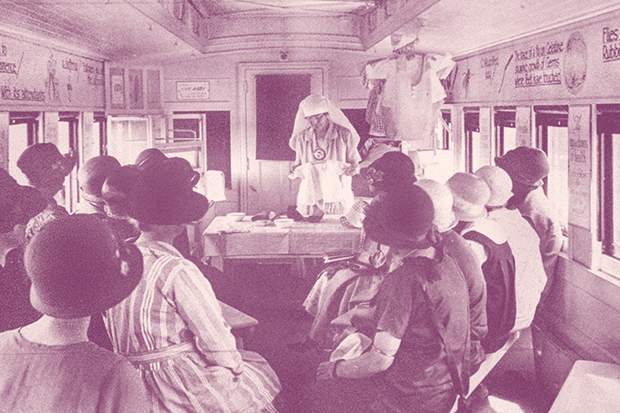

From 1924 to 1935 the Better Farming Train travelled country lines providing information to farmers, with carriages devoted to specific produce such as eggs or pigs.

A carriage was added to teach farmers’ wives ‘mothercraft’ and to conduct consultations. The Victorian Baby Health Centres Association appointed Sister Muriel Peck to give lectures and consultations on the train. She gave over 400 lectures, including slide lectures at night.

Sister Muriel Peck gives a demonstration on the Better Farming Train. Courtesy of the Public Records Office Victoria.

In its first three years, the infant welfare section of the train had approximately 23,000 visitors (Sheard 2007). The train made 38 tours until the Depression brought an end to its operation.

Sisters also gave demonstrations and lectures, and staffed display stands at Victorian agricultural shows.

The Travelling Baby Health Centre

Despite the Depression and the accompanying demise of the Better Farming Train, maternal and child health services to isolated rural mothers and their babies continued. In 1937 a custom-designed baby health centre van set off on its maiden voyage, with a baby health section in the front and sleeping quarters for two sisters in the rear (Crockett 2000).

Department of Infant Welfare Health van. Courtesy of the Public Record Office Victoria.

In a serious effort to reach more women in more remote parts of the bush, one-nurse vans were introduced from 1942. By 1944 four mobile units were visiting 84 country townships, covering 1700 miles (2735 kilometres) per fortnight (Victorian Heritage Database Report 2005).

City of Springvale mobile van, 1995. Courtesy of Public Record Office Victoria.

Stops were scheduled to coincide with towns’ market days or the arrival of a train from Melbourne, so farmers could pick up their mail and supplies at the same time (Crockett 2000).

The VBHCA van continued to operate until 1957 by which time most shires had agreed to establish permanent centres. The custom-built van was replaced by a Kombi van which serviced a reduced circuit until 1961.

Isolated country families showed their appreciation for the service with gifts to the sisters of fresh vegetables, fruit and meat which were some recompense for the conditions the sisters had to deal with: poor roads, flat tyres, vehicle breakdowns and dodging wildlife.

Said one rural mother of the difference the travelling service had made to her life:

‘My four eldest were born before 1937, when the first caravan came to the Mallee. Two of my babies died. I never knew what their crying meant... It’s not easy to bring up babies by guesswork.’

The Maternal and Child Health Line

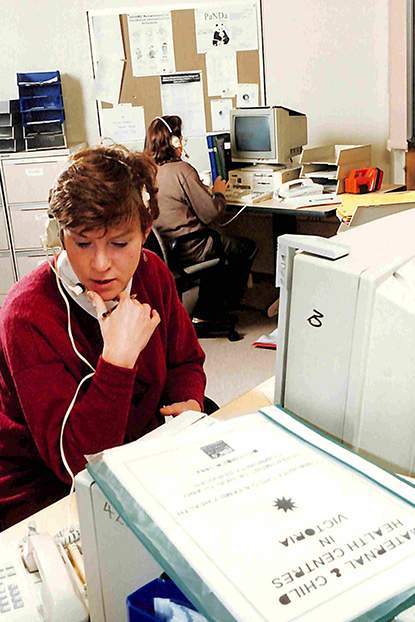

Maternal and Child Health Line, 1995. Courtesy of the Public Record Office Victoria.

The extraordinary dedication of Victoria’s maternal and child health nurses is exemplified by the beginnings of the telephone service, the Maternal and Child Health Line. From 1974–1988 maternal and child health nurses ran a voluntary telephone service, taking it in turns to receive calls in their own homes from 6pm until midnight.

The funded service began on Mothers Day 1991 and in 2000 the operating hours of the telephone service were extended to 24 hours/seven days per week.

The Enhanced Maternal and Child Health Service

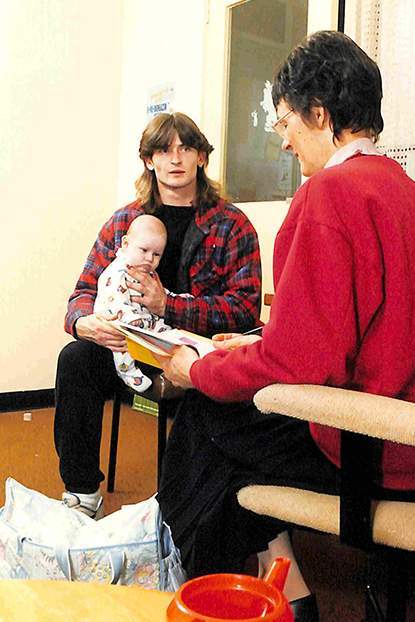

Father with baby and nurse, Shire of Yarra Ranges, 1995. Courtesy of the Public Record Office Victoria.

The introduction of the Enhanced Home Visiting Service in 2000 – now known as the Enhanced Maternal and Child Health Service – enabled nurses to provide more focused and intensive support to vulnerable families experiencing parenting difficulties and to children at risk of harm (Department of Human Services 2004).

The Victorian Maternal and Child Health Service has come a long way since Sister Muriel Peck was set up with a desk and one set of scales for weighing babies at the first centre in Richmond in 1917.

Mothers with babies weigh in. Circa 1960s. Courtesy of the Queen Elizabeth Centre.

From the time a maternal and child health nurse makes the first visit to the mother and baby in their home, she begins a relationship that can encompass dealing with everything from post-natal depression to identifying a child’s developmental delays.

In her working day, she may traverse language and cultural barriers, screen for domestic violence and mental health issues, give immunisations, advise on breast-feeding or simply reassure anxious first-time parents they’re doing a good job.

The Victorian Baby Health Centre Association was a common sight at many exhibitions in Melbourne. All aspects of infant welfare work were demonstrated to encourage mothers to attend baby health centres. Courtesy of the Queen Elizabeth Centre.

Since the early 1940s maternal and child health nurses have worked together as a professional association to improve Victoria’s Maternal and Child Health Service and advocate for their profession.

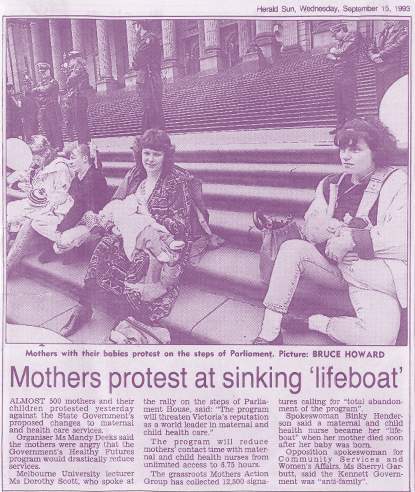

Mothers protest in 1993 against the Victorian Government’s changes to the Maternal and Child Health Service under the Healthy Futures program. Herald Sun, Wednesday 15 September 1993.

The Victorian Association of Maternal and Child Health Nurses has lobbied to maintain requirements for Victorian maternal and child nurses to have registered nurse and midwifery qualifications, plus a post-graduate diploma in child and family health. The association has also advocated for decent wages and working conditions for maternal and child health nurses.

Video: From baby weighing to life saving, part one.

VAMCHN has also established and advocated for the professional standards that make our Maternal and Child Health Service the ‘gold standard’ and underpin nurses’ preparedness for understanding and managing the health needs of babies, mothers and fathers.

Demonstrating baby massage. Courtesy of the Public Record Office Victoria.

In the 1990s under the Kennett Government, the Maternal and Child Health Service – delivered by local government – became an inadvertent target of the state government’s amalgamations of local government areas and requirement that half of all council services be subjected to compulsory competitive tendering.

Video: From baby weighing to life saving, part two.

Many consultants and council staff trying to ‘sell’ their maternal and child health services in the tendering process had little understanding of what maternal and child health nurses did and tended to perceive them as ‘baby weighers’ (Reiger and Keleher 2004).

For 100 years, Victorian parents have had access to advice and care for mother and baby at one of the most vulnerable times of their lives.

Over the years the nature of advice and some infant care practices have changed. In the 1920s, Dr Truby King, founder of the Plunket Society, demanded mothers oversee ‘regularity of all habits’ in their infants, advising that they must not allow '10 o'clock in the morning [to] pass without getting baby's bowels to move.’

Baby massage circle, Yarra Ranges Shire, 1995. Photo: Public Record Office Victoria.

Dr King directed expectant mothers to take nutritious food, breathe fresh air ('windows wide open all the time'), and exercise with vigour, including a two-hour daily walk whatever the weather (Olssen 1981).

Parents too have changed. First-time parents are generally older, fathers are more involved in parenting and with successive waves of migration and refugees seeking asylum in Victoria, maternal and child health nurses encounter parents with a range of cultural backgrounds.

Parents are also more educated than they were in 1917, and able to access information about health and baby care from experts and other parents online.

Video: The parents, part one.

The heart of the Maternal and Child Health Service remains the relationship between nurse and mother.

In 2014–15 Victoria’s maternal and child health nurses delivered 666,035 key ages and stages consultations with children ranging in age from newborn to 3.5 years (Victorian Department of Education and Training 2015).

In that year, there were 128,909 instances of nurses ‘counselling’ parents – giving them advice or information about their children’s vision, hearing, congenital anomalies, development, potentially disabling conditions, nutrition, dental care, communication, growth, illnesses and accidents.

Video: The parents, part two.

Parental approval

Evaluations of the Maternal and Child Health Service invariably elicit parents’ appreciation for the service. In a survey conducted in 2006 more than 95 per cent of parents said they were satisfied with the service and felt respected by their maternal and child health nurse (Department of Human Services 2006).

For Lisa – a sole parent who discovered three weeks before giving birth that her baby had a life-threatening kidney disease – visits from Enhanced Maternal and Child Health Service nurse Bernice Boland have been nothing less than a godsend.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Changes in Australia’s disease profile: a view of the twentieth century, Australia’s Health, 2000

Crockett, C. Save the Babies – the Victorian Baby Health Centres’ Association and the Queen Elizabeth Centre, Arcadia, 2000

Department of Education and Training, Maternal and Child Health Services Annual Report, 2014–15

Department of Human Services and MAV, Future Directions for the Victorian Maternal and Child Health Service, 2004

Flood, M. Baby Boon: The Infant Welfare Movement in Victoria, Victorian Historical Journal, Vol. 69, No. 1, June, 1998

Heritage Council of Victoria, Victorian Heritage Database Report, Former Baby Health Care Centre (Echuca), 2005

Keleher, H. and Reiger, K. Nurses on the market: the impact of neo-liberalism on the Victorian Maternal and Child Health Service, Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2004

Main, H. and Scantlebury, V., Report to the Minister of Public Health on the Welfare of Women and Children, 1926

Olssen, E. Truby King and the Plunket Society: An analysis of a prescriptive ideology, New Zealand Journal of History, 1981, Vol. 15, No. 1

Potter, B.M. The contribution of the Maternal and Child Health Nursing Special Interest Group to maternal and child health nursing, notes for the Maternal and Child Health Forum, 2000

Poulter, J. A tribute to Dame Kate Campbell, Victorian Baby Health Centres Association and the Queen Elizabeth Hospital for Mothers and Babies Annual Report, 1986

Sheard, H. All the little children – the story of Victoria’s baby health centres, MAV, 2007

Stanley, F. Child health since Federation, Year Book Australia 2001, Australian Bureau of Statistics

Victorian Baby Health Centre Association Annual Report, 1923–24

A special thank you to

The interviewees

Bernice Boland, enhanced maternal and child health nurse and Chair, Victorian Association of Maternal and Child Health Nurses

Marie Burgess, maternal and child health nurse and President, ANMF (Victorian Branch)

Dr Gay Edgecombe, former professor and clinical chair, Community Child Health Nursing, RMIT

Pamela Forsyth, former maternal and child health nurse

Kathleen Kehoe, former maternal and child health nurse

Lisa, client of Enhanced Maternal and Child Health Service

Jenny Mikakos MP, Victorian Minister for Families and Children

Toni Ormston, Manager, Maternal and Child Health Line

Barbara Potter AM, former maternal and child health nurse

Professor Emeritus Dorothy Scott OAM, former chair of child protection and former director, Australian Centre for Child Protection, University of South Australia.

Margaret Walshe, former maternal and child health nurse

And also

Marjolijn Alexander and Liz Jeffares from Bellfield Maternal and Child Health Centre

The 2017 Bellfield Maternal and Child Health Centre new parents group

James Bellew of Bee TV (video production)

Jorge de Araujo of Artificial Studios (photography)

Public Records Office of Victoria

Queen Elizabeth Centre

State Library of Victoria

Victorian Association of Maternal and Child Health Nurses